We sees opportunities from the calamities. RAH Worldwide Technology are urging you to join our efforts to solve this problems once and for all..

There are money to be made if you are a capitalists investors. For the others human raises, we will have a beautiful place to live in...

See our PYRO-FLOTILLA PROJECT Page

The

Great Pacific garbage patch, also described as the

Pacific trash vortex, is a

gyre of

marine debris particles in the central

North Pacific Ocean discovered between 1985 and 1988. It is located roughly between

135°W to

155°W and

35°N and

42°N.

[1] The patch extends over an indeterminate area of widely varying range depending on the degree of

plastic concentration used to define the affected area.

The patch is characterized by exceptionally high relative concentrations of pelagic plastics, chemical sludge and other debris that have been trapped by the currents of the North Pacific Gyre.[2] Its low density (4 particles per cubic meter) prevents detection by satellite photography, or even by casual boaters or divers in the area. It consists primarily of a small increase in suspended, often microscopic, particles in the upper water column.

Discovery

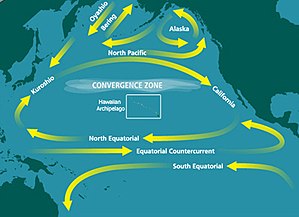

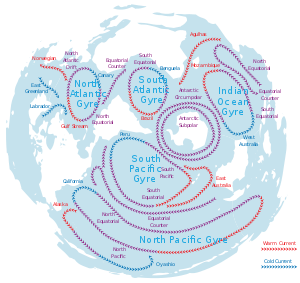

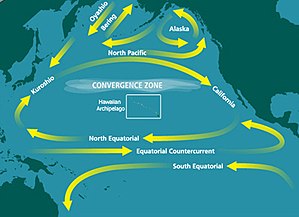

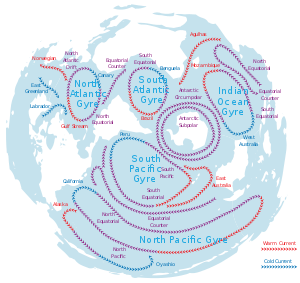

The Patch is created in the gyre of the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone

The great Pacific garbage patch was described in a 1988 paper published by the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States. The description was based on results obtained by several Alaska-based researchers between 1985 and 1988 that measured

neustonic plastic in the North Pacific Ocean.

[3]Researchers found high concentrations of marine debris accumulating in regions governed by ocean currents. Extrapolating from findings in the

Sea of Japan, the researchers hypothesized that similar conditions would occur in other parts of the Pacific where prevailing currents were favorable to the creation of relatively stable waters. They specifically indicated the North Pacific Gyre.

[4]

Charles J. Moore, returning home through the North Pacific Gyre after competing in the

Transpac sailing race in 1999, claimed to have come upon an enormous stretch of floating debris. Moore alerted the

oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer, who subsequently dubbed the region the "Eastern Garbage Patch" (EGP).

[5] The area is frequently featured in media reports as an exceptional example of

marine pollution.

[6]

The patch is not easily visible, because it consists of tiny pieces almost invisible to the naked eye.

[7] Most of its contents are suspended beneath the surface of the ocean,

[8]and the relatively low density of the plastic debris is, according to one scientific study, 5.1 kilograms per square kilometer of ocean area (5.1 mg/m

2).

[9]

Information

The north Pacific Garbage Patch on a continuous ocean map

It is thought that, like other areas of concentrated marine debris in the world's oceans, the Great Pacific garbage patch formed gradually as a result of ocean or marine pollution gathered by

oceanic currents.

[12] The garbage patch occupies a large and relatively stationary region of the North Pacific Ocean bound by the North Pacific Gyre (a remote area commonly referred to as the

horse latitudes). The gyre's rotational pattern draws in waste material from across the North Pacific Ocean, including coastal waters off North America and Japan. As material is captured in the currents, wind-driven surface currents gradually move floating debris toward the center, trapping it in the region.

There is no strong scientific data concerning the origins of

pelagic plastics.

[dubious – discuss][citation needed] In a study published in 2014,

[13] researchers sampled 1571 locations throughout the worlds oceans, and determined that discarded fishing gear such as buoys, lines, and nets accounted for more than 60%

[14] of the mass of plastic marine debris. The figure that an estimated 80% of the garbage comes from land-based sources and 20% from ships is derived from an unsubstantiated estimate.

[15] According to a 2011

EPA report, "The primary source of marine debris is the improper waste disposal or management of trash and manufacturing products, including plastics (e.g., littering, illegal dumping) ... Debris is generated on land at marinas, ports, rivers, harbors, docks, and storm drains. Debris is generated at sea from fishing vessels, stationary platforms and cargo ships."

[16] Pollutants range in size from abandoned fishing nets to

micro-pellets used in abrasive cleaners.

[17] Currents carry debris from the west coast of North America to the gyre in about six years,

[18] and debris from the east coast of Asia in a year or less.

[19][20]

Estimates of size

The size of the patch is unknown, because large items readily visible from a boat deck are uncommon. Most debris consists of small plastic particles suspended at or just below the surface, making it difficult to accurately detect by aircraft or satellite. Instead, the size of the patch is determined by sampling. Estimates of size range from

700,000 square kilometres (270,000 sq mi) (about the size of Texas) to more than 15,000,000 square kilometres (5,800,000 sq mi) (0.4% to 8% of the size of the Pacific Ocean), or, in some media reports, up to "twice the size of the continental United States".

[21] Such estimates, however, are conjectural given the complexities of sampling and the need to assess findings against other areas. Further, although the size of the patch is determined by a higher-than-normal degree of concentration of

pelagic debris, there is no standard for determining the boundary between "normal" and "elevated" levels of pollutants to provide a firm estimate of the affected area.

Net-based surveys are less subjective than direct observations but are limited regarding the area that can be sampled (net apertures 1–2 m and ships typically have to slow down to deploy nets, requiring dedicated ship's time). The plastic debris sampled is determined by net mesh size, with similar mesh sizes required to make meaningful comparisons among studies. Floating debris typically is sampled with a

neuston or

manta trawl net lined with 0.33 mm mesh. Given the very high level of spatial clumping in marine litter, large numbers of net tows are required to adequately characterize the average abundance of litter at sea. Long-term changes in plastic meso-litter have been reported using surface net tows: in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre in 1999, plastic abundance was 335 000 items/km

2 and 5.1 kg/km

2, roughly an order of magnitude greater than samples collected in the 1980s. Similar dramatic increases in plastic debris have been reported off Japan. However, caution is needed in interpreting such findings, because of the problems of extreme spatial heterogeneity, and the need to compare samples from equivalent water masses, which is to say that, if an examination of the same parcel of water a week apart is conducted, an order of magnitude change in plastic concentration could be observed.

[22]

In August 2009, the

Scripps Institution of Oceanography/

Project Kaisei SEAPLEX survey mission of the Gyre found that plastic debris was present in 100 consecutive samples taken at varying depths and net sizes along a 1,700 miles (2,700 km) path through the patch. The survey also confirmed that, although the debris field does contain large pieces, it is on the whole made up of smaller items that increase in concentration toward the Gyre's centre, and these '

confetti-like' pieces are clearly visible just beneath the surface. Although many media and advocacy reports have suggested that the patch extends over an area larger than the continental U.S., recent research sponsored by the

National Science Foundation suggests the affected area may be much smaller.

[22][23][24] Recent data collected from Pacific

albatross populations suggest there may be two distinct zones of concentrated debris in the Pacific.

[25]

Photodegradation of plastics

Washed up plastic waste on a beach in Singapore.

The Great Pacific garbage patch has one of the highest levels known of plastic particulate suspended in the upper water column. As a result, it is one of several oceanic regions where researchers have studied the effects and impact of plastic

photodegradation in the

neustonic layer of water.

[26] Unlike organic debris, which

biodegrades, the photodegraded plastic disintegrates into ever smaller pieces while remaining a

polymer. This process continues down to the

molecular level.

[27] As the plastic

flotsam photodegrades into smaller and smaller pieces, it concentrates in the upper water column. As it disintegrates, the plastic ultimately becomes small enough to be ingested by aquatic organisms that reside near the ocean's surface. In this way, plastic may become concentrated in

neuston, thereby entering the

food chain.

Some plastics decompose within a year of entering the water, leaching potentially toxic chemicals such as

bisphenol A,

PCBs, and derivatives of

polystyrene.

[28]

The process of disintegration means that the plastic particulate in much of the affected region is too small to be seen. In a 2001 study, researchers (including Charles Moore) found concentrations of plastic particles at 334,721 pieces per km

2 with a mean mass of 5,114 grams (11.27 lbs) per km

2, in the

neuston. Assuming each particle of plastic averaged 5 mm × 5 mm × 1 mm, this would amount to only 8 m

2 per km

2 due to small particulates. Nonetheless, this represents a high amount with respect to the overall ecology of the neuston. In many of the sampled areas, the overall concentration of plastics was seven times greater than the concentration of

zooplankton. Samples collected at deeper points in the water column found much lower concentrations of plastic particles (primarily

monofilament fishing line pieces).

[9]

Effect on wildlife and humans

Some of these long-lasting plastics end up in the stomachs of marine animals, and their young,

[5][29][30] including

sea turtles and the

black-footed albatross.

Midway Atoll receives substantial amounts of

marine debris from the patch. Of the 1.5 million

Laysan albatrosses that inhabit Midway, nearly all are likely to have plastic in their

digestive system.

[31] Approximately one-third of their chicks die, and many of those deaths are due to being fed plastic from their parents.

[32][33] Twenty tons of plastic debris washes up on Midway every year with five tons of that debris being fed to albatross chicks.

[34]

Besides the particles' danger to wildlife, on the

microscopic level the floating debris can absorb

organic pollutants from seawater, including

PCBs,

DDT, and

PAHs.

[35] Aside from toxic effects,

[36] when ingested, some of these are mistaken by the

endocrine system as

estradiol, causing hormone disruption in the affected animal.

[33] These toxin-containing plastic pieces are also eaten by

jellyfish, which are then eaten by fish.

Many of these fish are then consumed by humans, resulting in their ingestion of toxic chemicals.

[37]

Marine plastics also facilitate the spread of invasive species that attach to floating plastic in one region and drift long distances to colonize other ecosystems.

[17]

While eating their normal sources of food, plastic ingestion can be unavoidable or the animal may mistake the plastic as a food source.

[38][39][40][41][42]

Research has shown that this plastic marine debris affects at least 267 species worldwide.

[43]

Controversy

There has been some controversy surrounding the use of the term "garbage patch" and photos taken off the coast of Manila in the Philippines in attempts to portray the patch in the media often misrepresenting the true scope of the problem and what could be done to solve it. Dr Angelicque White, Associate Professor at Oregon State University, who has studied the "garbage patch" in depth, warns that “the use of the phrase ‘garbage patch’ is misleading. ... It is not visible from space; there are no islands of trash; it is more akin to a diffuse soup of plastic floating in our oceans." In the article Dr. White and Professor Tamara Galloway, from the University of Exeter, call for regulation and cleanup and state that the focus should be on stemming the flow of plastic into the ocean from coastal sources.

[44]

Cleanup research

In April 2008, Richard Sundance Owen, a building contractor and scuba dive instructor, formed the Environmental Cleanup Coalition (ECC) to address the issue of North Pacific pollution. ECC collaborates with other groups to identify methods to safely remove plastic and

persistent organic pollutants from the oceans.

[45][46] The

JUNK raft project was a trans-Pacific sailing voyage from June to August 2008 made to highlight the plastic in the patch, organized by the

Algalita Marine Research Foundation.

[47][48][49]

Project Kaisei, a project to study and clean up the garbage patch, launched in March 2009. In August 2009, two project vessels, the

New Horizon and the

Kaisei, embarked on a voyage to research the patch and determine the feasibility of commercial scale collection and recycling.

[50] The SEAPLEX expedition, a group of researchers from

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, spent 19 days on the ocean in August, 2009 researching the patch. Their primary goal was to describe the abundance and distribution of plastic in the gyre in the most rigorous study to date. Researchers were also looking at the impact of plastic on

mesopelagic fish, such as

lanternfish.

[51][52] This group utilized a dedicated oceanographic research vessel, the 170 ft (52 m) long

New Horizon.

[53][54]

In 2012, Miriam C. Goldstein, Marci Rosenberg, and Lanna Cheng wrote:

Plastic pollution in the form of small particles (diameter less than 5 mm) — termed ‘

microplastic’ — has been observed in many parts of the world ocean. They are known to interact with biota on the individual level, e.g. through ingestion, but their population-level impacts are largely unknown. One potential mechanism for microplastic-induced alteration of pelagic ecosystems is through the introduction of hard-substrate habitat to ecosystems where it is naturally rare. Here, we show that microplastic concentrations in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) have increased by two orders of magnitude in the past four decades, and that this increase has released the pelagic insect

Halobates sericeus from substrate limitation for oviposition. High concentrations of microplastic in the NPSG resulted in a positive correlation between H. sericeus and microplastic, and an overall increase in H. sericeus egg densities. Predation on H. sericeus eggs and recent hatchlings may facilitate the transfer of energy between pelagic- and substrate-associated assemblages. The dynamics of hard-substrate-associated organisms may be important to understanding the ecological impacts of oceanic microplastic pollution.

[55]

The Goldstein et al. study compared changes in small plastic abundance between 1972-1987 and 1999-2010 by using historical samples from the Scripps Pelagic Invertebrate Collection and data from SEAPLEX, a NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer cruise in 2010, information from the Algalita Marine Research Foundation as well as various published papers.

[56]

At TEDxDelft2012,

[57][58] Dutch Aerospace Engineering student

Boyan Slat unveiled a concept for removing large amounts of marine debris from the five oceanic gyres. Calling his project

The Ocean Cleanup, he proposed to use surface currents to let debris drift to specially designed arms and collection platforms. Operating costs would be minimal and the operation would be so efficient that it might even be profitable. The concept makes use of floating booms, that divert rather than catch the debris. This way

bycatch would be avoided, although even the smallest particles would be extracted. According to Slat's calculations, a gyre could be cleaned up in five years' time, collecting at least 7.25 million tons of plastic across all gyres.

[59] He also advocated "radical plastic pollution prevention methods" to prevent gyres from reforming.

[59][60]

Method, a producer of household products, markets a dish soap whose container is made partly of recycled ocean plastic. The company sent crews to Hawaiian beaches to recover some of the debris that had washed up.

[61]Artists such as

Marina DeBris use trash from the garbage patch to create

trashion, or clothes made out of trash. The main purpose is to educate people about the garbage patch.

The 2012 Algalita/

5 Gyres Asia Pacific Expedition began in the

Marshall Islands on 1 May, investigated the little-studied Western Pacific garbage patch, collecting samples for the 5 Gyres Institute, Algalita Marine Research Foundation and several other colleagues, including NOAA, SCRIPPS, IPRC and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. From 4 October – 9 November 2012, the Sea Education Association (SEA) conducted a research expedition to study plastic pollution in the North Pacific gyre. A similar research expedition was conducted by SEA in the North Atlantic Ocean in 2010. During the Plastics at SEA 2012 North Pacific Expedition, a total of 118 net tows were conducted and nearly 70,000 pieces of plastic were counted to estimate the density of plastics, map the distribution of plastics in the gyre, and examine the effects of plastic debris on marine life.

[62]

On 11 April 2013, in order to create awareness, artist

Maria Cristina Finucci founded The

Garbage Patch State at

UNESCO[63] –Paris in front of Director General

Irina Bokova. It was the first of a series of events under the patronage of

UNESCO and of the Italian Ministry of the Environment.

[64] In 2015, The

Ocean Cleanup project was a category winner in the

Design Museum's 2015 Designs of the Year awards.

[65] A fleet of 30 vessels, including a 32 metres (105 ft) mothership, took part in a month-long voyage to determine how much plastic is present using trawls and aerial surveys.

[65]

In 2016, plans are in the concept stage to create floating

Oceanscrapers, made from the plastic found in the Great Pacific garbage patch.

[66] In June, The Ocean Cleanup project launched a prototype boom, nicknamed Boomy McBoomface, off the coast of the

Netherlands in the

North Sea, with the intention that if tests with the 100 meter prototype go well plans to develop a 100 kilometer long scaled up version that would then be deployed in the Pacific would go forward.

[67]